Why did I pick this topic for today’s blog? Well, I ran across a BBC story (click here to read the article) about the women in the Women’s Auxiliary Air Force (WAAF), a British military service during World War II. The article focuses on three women assigned to the RAF Biggin Hill air base during the Battle of Britain. These women were awarded the Military Medal (MM) while only six women received the MM during World War II.

I’m always intrigued with stories of women’s contributions during World War II and other historical events. Some of the past blogs include Women Agents of the SOE (click here to read), Killed in the Service of Her Country (click here to read), The Ten Percenters (click here to read), The Wrens (click here to read), The White Mouse (click here to read), and The Night Witches (click here to read).

Biggin Hill is likely a topic that our British friends and historians know very well. However, outside of England, the story of Biggin Hill during the war may be a topic that is not well-known. So, apologies to those of you who are familiar with RAF Biggin Hill and the role it played during the Battle of Britain. If you have comments, suggestions, or perhaps other information you think should be added to this blog, please contact me.

Did You Know?

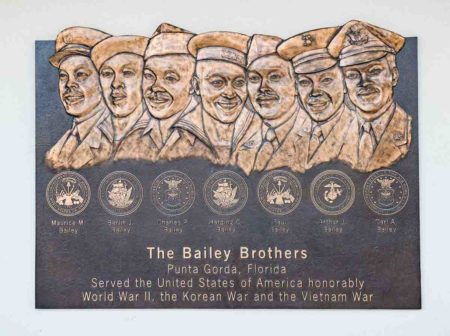

Did you know that I live in Punta Gorda, Florida and have you ever heard of Punta Gorda? Well, our little town dates to 1884 and Punta Gorda has a very strong and proud history with all its citizens. One of the families that settled here in 1905 was Archie and Josephine Bailey. The Baileys were African American, and they had eleven children: nine boys and two girls.

The oldest boy, Maurice (1906−1990), enlisted in the army and served in World War II and the Korean conflict. He is buried in Arlington National Cemetery. Berlin (1912−1997) served in the navy in the Pacific theater during World War II. Following the war, Berlin returned to Punta Gorda and was elected to the city’s planning commission. Charles (1918−2001) enlisted in the U.S. Army Air Corps and became the nation’s first African American armed forces pilot from Florida. He joined the 332nd Fighter Group and the 99thFighter Squadron commonly known “The Tuskegee Airmen.” Second Lt. Bailey, flying either a P-40 or P-51, flew 133 combat missions in Northern Africa and Europe as part of the “Red Tail Squadron.” After the war, Charles obtained his college degree and became a teacher. Harding (1920−1984) enlisted in the navy and served in the Atlantic theater. He became a school principal after the war. Paul (1922−1987) joined the army in 1943 and was a chaplain’s assistant in the Pacific theater. Paul obtained a music degree and became a high school music teacher. Arthur (1925−1959) enlisted in the U.S. Marines in February 1945 and saw action in the Pacific theater. Carl (1929−1957), the youngest son, served in the U.S. Air Force and flew F-84 Thunderjets. He was one of only two African American fighter pilots from Florida during the Korean conflict. Tragically, Carl died in an automobile accident.

Collectively, these sons of Mr. and Mrs. Bailey are known as “The Fighting Bailey Brothers.” Today, five of the brothers are interned at the Lt. Carl A. Bailey Cemetery in Punta Gorda. The passenger terminal at the Punta Gorda Airport is named in their honor.

Click here to watch the video Meet the “Fighting Bailey Brothers.”

Biggin Hill

The town of Biggin Hill is located in the south-east of Greater London. It is situated on one of the highest points of Greater London and its airport, Biggin Hill Airport, supports general aviation needs including private and business jet traffic. Although large enough for Boeing 737 aircraft, the airport is not a commercial (i.e., paying passengers) airport.

Click here to watch Biggin Hill Then & Now Slideshow

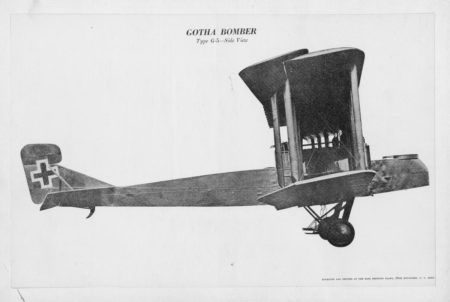

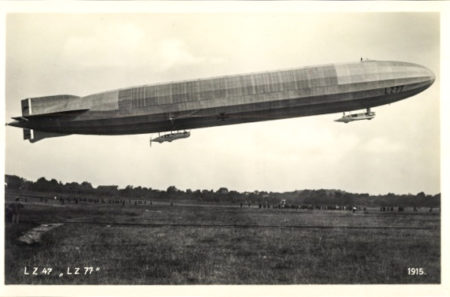

Biggin Hill Airport sits on the site of the former RAF Biggin Hill air base. The airfield was originally established in 1916 by the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) for use during World War I for wireless experiments. A year later, it was incorporated into the London Air Defense Area, responsible for defending London against attacks by German Zeppelins and Gotha bombers. During the interwar years, the base was used for training, developing experimental aircraft and instruments, and night flying.

The Battle of Britain

The Battle of Britain took place between 10 July and 31 October 1940. It was Hitler’s prelude to invading England (i.e., Unternehmen Seelöwe, or “Operation Sea Lion”) and it pitted Hermann Göring’s Luftwaffe against the Royal Air Force (RAF). Hitler would not invade unless the Germans attained air and sea superiority. Over the three-month period, RAF Fighter Command defeated the Nazi Luftwaffe and forced Hitler to abandon his invasion plans on 7 September 1940. Hitler then changed his tactics to bombing London at night which became known as “The Blitz.”

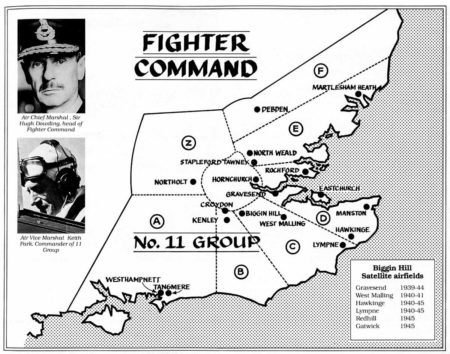

One of the reasons for the successful defense of England was the highly effective air defense system that brought together technology such as radar, ground defenses, and superior fighter aircraft. (Göring later admitted it was British radar that defeated the Luftwaffe.) The RAF was organized into four geographical areas known as “Groups.” These were further divided into sectors with a main fighter airbase known as “Sector Station.” Each was provided with an operations room acting as a hub for incoming and outgoing information. Using this information, airborne pilots and aircraft could be directed to advantageous positions. With the technical and tactical support of its operations rooms, Fighter Command was able to efficiently and effectively use its limited resources against the Luftwaffe.

There were several phases to the Battle of Britain. Initially, the Germans focused on attacking coastal targets and British shipping in the English Channel. By mid-August, attacks moved inland and concentrated on hitting the airfields and communications centers. A third phase began at the end of August and first part of September when the Luftwaffe intensified their attacks on the airfields and in particular, those in the south-east. As they say in American football, “The defense bent but did not break.”

Nearly three thousand men flew missions during the battle. They came from across the U.K. and the Commonwealth. However, foreign pilots contributed in a big way. They were Polish, French, Belgian, Americans, and from Czechoslovakia. The No. 303 Fighter Squadron was primarily Polish, and it became Fighter Command’s squadron with the most kills (126) of “Adolfs.”

The fighter pilots were supported by ground crew, factory workers, Observer Corps (there were more than one thousand observation posts), anti-aircraft gunners, searchlight operators, and barrage balloon crews. Churchill’s “The Few” were supported by many.

Click here to watch The Polish Pilots of the Battle of Britain.

RAF Biggin Hill

When England declared war against Germany in September 1939, there were two squadrons based at RAF Biggin Hill: nos. 32 and 79. They were shortly joined by Squadron no. 601 that flew the Bristol Blenheim, the first twin-engine planes to fly out of Biggin Hill. The air base was a controlling station for No. 11 Group, Fighter Command and due to its location, was responsible for the defense of Southeast England and London. While it was one of the bases that played a decisive role defending London against the German fighter planes and bombers sent by Hitler to destroy the city, the air base bore the brunt of German aerial assaults, especially one brutal attack in August.

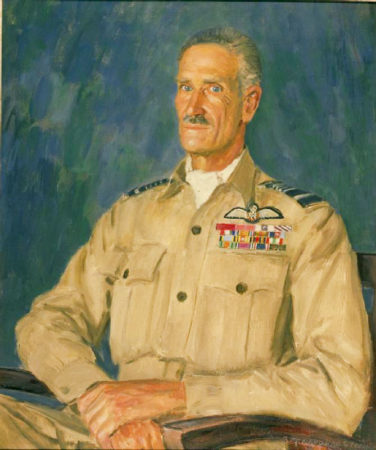

Air Chief Marshal, Sir Hugh Dowding (1882−1970) was head of RAF Fighter Command and generally credited with defeating Hermann Göring’s Luftwaffe. Air Vice Marshal Sir Keith Park (1892−1975) was the commander of No. 11 Group and after the war became known as “The Defender of London.” Because of its prominent role during the Battle of Britain, RAF Biggin Hill gained the nickname, “The Strongest Link” and its crest later incorporated a chain into its design.

Click here to watch WW2: How the Dowding System Made the Battle of Britain a Success.

The squadrons based at RAF Biggin Hill primarily flew the Supermarine Spitfire and the Hawker Hurricane aircraft. The Spitfires were primarily used to intercept German fighter planes such as the Messerschmitt Bf 109s while the Hurricanes went after enemy bombers. Despite popular opinion that the Spitfire won the Battle of Britain, the Hurricanes accounted for about sixty percent of all German aircraft losses. The squadrons claimed to have downed 1,400 enemy aircraft during the battle against a total loss of 453 RAF Biggin Hill based aircrew.

The Germans knew the importance of RAF Biggin Hill and its significant role in destroying their aircraft. Between August 1940 and January 1941, the British airfield was attacked twelve times by German bombers. The first bombing on 18 August lasted ten minutes with five hundred bombs dropped by the Luftwaffe. (The ground crews had the runway repaired within a day.) The bombs destroyed workshops, stores, barracks, WAAF quarters, and hangers. Thirty-nine people were killed on the ground.

During the Battle of Britain, there were seven sectors: A, B, C, D, F, Y, and Z. RAF Biggin Hill was sector headquarters for Sector C (RAF Hawkinge and RAF Friston were included in Sector C). Headquarters for No. 11 Group was located at RAF Uxbridge. Its operations center was underground in what is today called the “Battle of Britain Bunker.”

Battle of Britain Bunker

Sixty feet (i.e., seventy-six steps) below the surface of RAF Uxbridge is an underground operations room. Fighter aircraft operations for No. 11 Group during the Battle of Britain and the war were conducted out of this room. Air Vice Marshal Park did not use the bunker as his headquarters. However, he did personally command RAF forces from here on 13 August 1940 (“Adlertag”), 18 August (“The Hardest Day”), and 15 September (“Battle of Britain Day”). While at RAF Uxbridge, Park stayed in a house opposite to the bunker entrance. The house was demolished but a door he used to get to the bunker and a garden wall were retained.

In addition to the map table where locations of friendly and enemy aircraft were plotted and tracked, the operations room including an electronic “tote” board. Each sector was represented, and a series of lights was used to indicate each squadron’s current status (i.e., “At Standby,” “Enemy Sighted,” and “Ordered to Land”). All information was sent by Fighter Command headquarters or each of the sector stations by telephone. By December 1940, the plotting system of wooden markers and croupier-style pushing sticks were replaced with metal markers and magnetic sticks. The tote board’s lights were replaced with a slat-board system.

Three days after Hitler ordered RAF airbases to be targeted, and immediately after a visit to RAF Biggin Hill, Prime Minister Winston Churchill coined the phrase, “Never in the field of human conflict was so much owed, by so many, to so few.” (Four days later, Churchill gave his famous speech to the House of Commons where he used this phrase.) The bunker was used after the Battle of Britain for the defense of London during the Blitz as well as being heavily involved with the operations of D-Day on 6 June 1944.

Click here to watch Churchill at Biggin Hill (1951).

Today, the bunker is run by Hillingdon Council, and it is considered a heritage site. A visitor center and its six rooms are located above the bunker. Among the collections, exhibits, and oral histories, it documents the story of three RAF Biggin Hill WAAFs who were awarded the Military Medal for valor. Click here to visit the web-site.

Women’s Auxiliary Air Force (WAAF)

Sgt. Joan Mortimer, Cpl. Elspeth Henderson, and Sgt. Helen Turner were teleprinter operators at RAF Biggin Hill on 30 August 1940 when the Luftwaffe bombs rained down on the airbase. Everyone was ordered to leave and take shelter. The three women stayed at their posts and continued their jobs. They were determined to protect the men and women on the ground as well as in the sky. Mortimer ran outside to set red flags where unexploded bombs sat on the runway. The three WAAFs were awarded the Military Medal (MM) but it was a controversial honor.

The Women’s Auxiliary Air Force was formed in June 1939. Women volunteers (conscription of women did not begin until 1941) were trained in aircraft maintenance, communications duties, and to pack parachutes. Like the United States, women were not allowed to enter combat or serve as aircrew. However, women pilots were utilized in the Air Transport Auxiliary (ATA) to transport aircraft around the country thus freeing up men for duty as combat pilots. (click here to read the blog, Killed in the Service of Her Country) WAAFs also performed in areas such as analyzing aerial reconnaissance photographs, codes and ciphers (e.g., Bletchley Park), and intelligence operations. They served at airfields, balloon barrage sites, and radar stations across the United Kingdom. WAAFs were represented in the British-led Special Operations Executive (e.g., Noor Inayat Khan, Yolande Beekman, and Diana Rowden, among many others).

Click here to watch WAAF Mechanics Work to Keep RAF Flying (1942).

The MM was established in 1916 and awarded to individuals for acts of bravery (with bars added for subsequent acts of bravery). Between 1916 and 1993 (when the medal was discontinued), a total of 132,169 medals and 6,167 bars were awarded. During World War II, 15,225 medals and 178 bars were given for bravery under enemy fire. Only 146 medals were awarded to women during the seventy-seven years of its existence and only six WAAFs were honored during World War II. Why were the MMs awarded to six women controversial? Because they were women. At time, the MMs were considered to be a “man’s award.”

Postwar

After the war, RAF Biggin Hill was used by the RAF’s Transport Command and then regular and reserve squadrons. By 1958, the base ceased being used as an operational RAF station and it was converted to a RAF Officer and Aircrew Selection Center. As time went on, more civilian light aviation operations relocated to the former RAF airbase. In 1972, the London Borough of Bromley voted to purchase the airport.

Situated within the boundaries of the airport is St. George’s Chapel of Remembrance. Built in 1951, the chapel is a memorial to the aircrew who died while flying out of Biggin Hill Sector. Replicas of a Spitfire and Hurricane mark the entrance to the chapel. The “North Camp” (west of the main runway) contains former RAF buildings including the Sergeant’s Mess and several barrack blocks.

Biggin Hill Memorial Museum

You can visit the RAF Biggin Hill Memorial Museum in Kent. It was established to honor and remember all of those who served at RAF Biggin Hill, including three women honored with the MM. Click here to visit the museum web-site.

The exhibition, “Women & War: Hidden Heroes of World War Two” will run at Biggin Hill Memorial Museum until late 2023.

The museum and former air base are easily reached via a seventeen-minute train ride from Victoria Station.

Click here to watch (WWII) RAF Biggin Hill Museum Opens (UK).

★ Learn More About Biggin Hill ★

Bungay, Stephen. The Most Dangerous Enemy: A History of the Battle of Britain. London: Aurum Press, 2000.

Escott, Beryl. The WAAF. London: Shire Library, 2008.

Escott, Beryl. Women in Air Force Blue: The story of women in the Royal Air Force from 1918 to the present day. Somerset: P. Stephens, 1989.

Escott, Beryl. Our Wartime Days: The WAAF in World War II. Stroud: Sutton Publishing Ltd., 1993.

Halpenny, Bruce Barrymore. Action Stations: 8. Military Airfields of Greater London. Somerset, U.K.: Haynes Publishing Group, 1993.

Ogley, Bob. Ghosts of Biggin Hill. Westerham: Froglets Publications, 2001.

Turner, John Frayn. The WAAF at War. Barnsley: Pen and Sword Aviation, 2011.

Click here and here to learn more about Charles P. Bailey. Sr.

Disclaimer:

There may be a chance that after we publish this particular blog, the video links associated with the blog are no longer accessible. We have no control over this. Many times, whoever posts the video has done so without the consent of the video’s owner. In some cases, it is likely that the content is deemed unsuitable by YouTube. We apologize if you have tried to access the link and you don’t get the expected results. Same goes for internet links.

What’s New With Sandy and Stew?

In a recent blog I mentioned that we were finished with traveling for the year. Well, I didn’t lie when I wrote that. However, in the meantime, we signed up for a transatlantic cruise in mid-October. It is with Holland America (at 68 years-of-age, I’m quite certain we will be the youngest on board) and the cruise celebrates the 150th anniversary of the first transatlantic voyage of the first ms Rotterdam. We sail out of Rotterdam, Netherlands and after a couple of days, venture out into the Atlantic Ocean where we will sail into New York City after seven days. I’ve always wanted to stand on the deck in the early morning as the ship enters New York City harbor. I will try and imagine what the foreign refugees and immigrants felt like watching the Statue of Liberty for the first time and knowing America would be their new home.

Thank you to all of you who subscribe to our bi-weekly blogs. It seems there isn’t a day that goes by where we don’t increase our readership. Please let your history buff friends and family members know about our blog site and blogs.

Someone Is Commenting On Our Blogs

I’d like to thank all of you who wrote us about the two blogs regarding our two week “holiday” in Paris and the U.K. It seems for some, our comments assisted them in their European trip. It’s always nice to know that our blogs can occasionally add value.

We also heard from three or four people about the blog, The SS City of Benares (click here to read). These folks were clearly experts on this topic and added valuable information that Sandy went back and updated the blog. I was able to introduce several of them to one another and I’m certain their research will benefit from the shared information.

If there is a topic you’d like to see a blog written about, please don’t hesitate to contact me. I love hearing from you so keep those comments coming.

Share This:

Follow Stew:

Find Stew’s books on Amazon and Apple Books.

Please note that we do not and will not take compensation from individuals or companies mentioned or promoted in the blogs.

Walks Through History

Walks Through History

Copyright © 2022 Stew Ross

Another great blog entry. I would add one thing that contributed to the RAF’s victory at the Battle of Britain–British Air Ministry-100.

(If I may be so bold as to quote from my soon to be published novel, “The Hunt for the Peggy C.”)

The BAM 100-octane aviation fuel, developed by Standard Oil of New Jersey, gave the modified Merlin engines of British Spitfires and Hurricanes thirty percent more horsepower for taking off and climbing. They also could fly 25-34 miles-per-hour faster than they did before the Blitz, an improvement in performance that startled and befuddled German pilots.

Shortly after the Battle of Britain ended, the RAF’s Air Chief Marshal Arthur Tedder said publicly that three things led to victory: the bravery and skill of the pilots, the engines Rolls Royce made, and “the availability of suitable fuel.”

The Germans quickly figured out what he meant when they discovered the fuel—dyed a distinctive green so it wouldn’t be confused with other fuels—in a downed Spitfire. But they couldn’t adapt their warplanes’ engines to the higher octane fuel, and were stuck with using the less efficient 87-octane gasoline, largely derived from coal gasification.

Good to hear from you again John. Thanks for the nice comment about the blog. I appreciate this “new” information. I will add it to the blog for future readers to learn about. I haven’t really focused on the British and in particular, the RAF. I really should do this. Thanks for the push! Talk soon. STEW